Think back to when you were a teenager, or if you are a teenager, listen up =), as teenagers, we had a certain amount of life experience, and we had seen our parents make a certain amount of mistakes. Since the age of reason, since around eight years old, we had begun to develop our own ability to discover the truth. At some point, we were tempted to strike out on our own and reject anything that we did not yet understand. When we reach this point, sometimes as a teenager and sometimes earlier, we are tempted to reject some of the truths that our parents hold; but could it be that because of their longer life experience, there are still truths outside our grasp, truths which we should hold on to out of trust, out of faith? The mystery of the Eucharist is one such truth, one such mystery, which our ultimate parent, God the Father, shares through the words of Jesus and through our mother, the Church, from generation to generation, as it reaches us today. This Eucharist is the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ.

Think back to when you were a teenager, or if you are a teenager, listen up =), as teenagers, we had a certain amount of life experience, and we had seen our parents make a certain amount of mistakes. Since the age of reason, since around eight years old, we had begun to develop our own ability to discover the truth. At some point, we were tempted to strike out on our own and reject anything that we did not yet understand. When we reach this point, sometimes as a teenager and sometimes earlier, we are tempted to reject some of the truths that our parents hold; but could it be that because of their longer life experience, there are still truths outside our grasp, truths which we should hold on to out of trust, out of faith? The mystery of the Eucharist is one such truth, one such mystery, which our ultimate parent, God the Father, shares through the words of Jesus and through our mother, the Church, from generation to generation, as it reaches us today. This Eucharist is the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ.

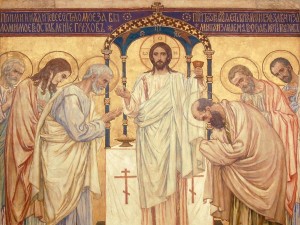

When we were children, and in catechism for first Holy Communion, the Church only expected us to see with the eyes of faith that what appeared to be bread and wine, was not ordinary, it was special, that it was actually God. As we become adults, we have opportunities to deepen our understanding of the Eucharist, and I’d like us to take this opportunity today. This week, I was reading a letter written to us by our Holy Father, St. John Paull the 2nd in the year 2003; it is called “Church of the Eucharist.” In it he encouraged our “critical thinking”, our striving after understanding of this great mystery which stands at the center of God’s love for us. Before we apply our reason, let us first know the facts we receive from Scripture. Jesus said at the last supper, “This is my Body and my Blood which will be given up for you” and then “Do this in memory of me.” He was telling us to come together in worship, to change ordinary bread and wine into his Body and Blood, and then to consume them, to consume his very self until he comes again.

St. Thomas Aquinas, around the year 1250, applied his reason, his critical thinking, to this great mystery. He applied “Aristotelian Metaphysics” an understanding that everything we see and touch, everything “material”, is matter and accidents. We can think of it this way; let’s imagine a painting which the painter intends for us to consume. The painter takes some cooked sweet potatoes and mashes them into a thin sheet, making a “canvas” for the painting. He then takes colors, food colors you know, that you can buy at the store, that can be painted upon the sweet potato canvas. The colors provide no nutritional value, they only make the sweet potato sheet appear as something, let’s say he paints it just as it appears to him, like sweet potatoes that have been cooked and mashed into a sheet. Now let’s say he lifts the painting from the sheet, the paint alone, and places it on top of something else, a sheet made out of zucchini. Since the paint is now on top of the zucchini sheet, it still appears as a sheet of sweet potatoes. It appears as if the zucchini canvas is a sheet made out of sweet potato, but it isn’t. The paint, the accidents, the appearance has remained the same, but the underlying substance, the canvas, the sheet, the the matter upon which the appearances rest, has changed. This shows the difference between matter and accidents. What a thing actually is, its substance, its matter, is like the canvass sheet upon which accidents lay. Accidents are like the paint which don’t affect what a thing is, but only what they appear to be. At every Mass, at some moment during the Eucharistic prayer, this extraordinary change happens before our very eyes; the matter of the bread and wine, the canvas, changes while the paint, the accidents, remain the same.

Now the Eucharist is different than the example of the painter. In our example we are limited by what a painter is able to do. Instead of God swapping the canvas of the bread with the canvas of his Son, God has the power to actually change one canvas into another. A painter cannot do this. He cannot make sweet potatoes become zucchini. Never mind the fact that a painter also probably can’t lift the paint from the canvas to apply it to another. No, our example is faulty, but it help us understand what is happening. While the paint remains, while the appearance or accidents of the bread and wine remain, God is able to change the underlying substance, the matter, the substance of the bread INTO the Body of his Son. God is able to change one canvas into another, while the paint does not change. He changes the matter of the created world into the matter of his Son’s flesh, the same flesh which was given birth to by the Virgin Mary, the same flesh which suffered, died, and was resurrected to new life. Even though the Eucharist has the “accidents”, the “appearance” of bread and wine, we know because of Scripture, that it is no longer ordinary bread or wine, it is no longer bread or wine at all, it is our resurrected Lord, Jesus Christ. Our parents, God the Father, and our Mother the Church has shared this truth with us. The Father has shared this with us through the words of his Son in Scripture. And our Mother shares this with us through the Tradition of the saints who have lived since the time of Christ, including those whom we have consulted today, St. John Paul the 2nd and St. Thomas Aquinas.

If we are teenagers, should we accept the testimony of our parents? Being curious we might consider what would happen if we dug into the molecular and atomic structure of the Eucharistic host, if we placed it under a powerful microscope. We would still find the appearance of bread. No matter how deep we dig into the layers of paint, we will only see more paint; that’s the depth of God’s power. Christ is in a sense hiding behind the appearances, because he is humble and respects our freedom to cooperate with his grace and choose to listen to him in faith or not. This is a similar act of faith he asked the first disciples to make. To them he only “appeared” as a man, but they had to see with faith beyond the appearance, to recognize that he was a divine person, the Son of God, which had become man through an extraordinary act, by birth through a virgin. In our case, we see with faith the same divine person, the same Son of God, now as a resurrected man, under the appearance, under the paint, of bread and wine. Like the disciples, our parents ask us to receive him in faith, the faith that God gave the disciples, and the faith that he gives us today. It is through the Eucharist, that Christ is present in us, in our families, to the poor, and throughout the world.